In the last week, I’ve seen and been sent one particular essay multiple times. It’s called “Your phone is why you don't feel sexy,” written by NYC-based writer and comedian Catherine Shannon in July 2024. Look, I love a good viral essay—especially one that grapples with how technology is enshittifying humanity. As I continue my Instagram sabbatical (I’ll admit to logging in a few times for strictly professional reasons), I’m actively trying to expand what information I’m taking in and leaving out. I was excited to hear why phones are why we’re not feeling sexy, but within minutes of starting the essay, I had to text the link to my friend Eliot, a critic who works in digital media and is also deeply skeptical of most of the modern internet.

“I’m reading through it after getting three people recommending it and parts are ok but it’s also kind of a mess so I need to discuss it with you lol.” After we both read through it all, we reached two conclusions. The first was that the vibes were incredibly off, and the second was that we absolutely needed to collaborate on a critique. Let me just be very clear before you start scrolling that this is not a takedown of the writer; it is a critique of the argument being presented in the essay. I’d argue that more criticism leads to more fruitful discussion and, honestly, a more exciting internet to exist in.

PS: It’s my birthday today, I’ve just arrived at a five-star spa hotel in a small Polish city, and I plan to go for a swim and sauna after this is published.

Welcome to Public Service.

“Research isn’t really my thing,” and honey, it shows.

Chris: Let’s just jump right into it. Calling a wildly hyperbolic assertion a “statement of fact,” claiming that no citation is needed, and then proceeding to brag about your disinterest in doing research used to be the bread and butter of the post-truth right-wingers. Now, apparently, it’s the secret sauce to starting a viral Substack essay. Pretend to be shocked when I say “Your phone is why you don't feel sexy” is a mess from start to finish.

Eliot: They say we need to open the schools but this is honestly an emergency, especially since almost every link is strictly to other posts of hers. Circling back to her own writing to support her own unresearched argument makes it so that the piece neither works as an essay proper or personal essay. The point ends up being “my phone [allegedly] makes me feel inadequate,” but without ever actually discussing why exactly. In today’s information economy, presenting your POV before making your point is seen as a marker of authenticity. But it’s a long way from that to opening up your polemic with, “I don’t need to cite anything, and anyways even if that was important, I also can’t be bothered to research.”

Chris: Before we dig in too much, let me just say (again) that this isn’t a hit piece on the author. Writing is hard and doing research is tedious, so it will always be easier to coast on vibes and surface-level insights. Still, it’s sad to see an interesting point about sexiness buried underneath the rubble of laziness.

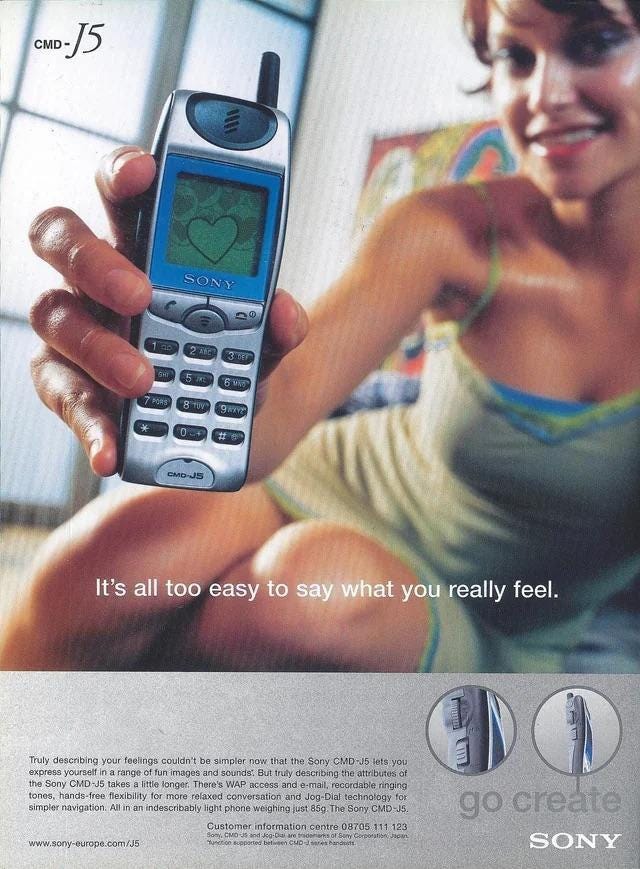

Eliot: It’s vibes-based, and like, I get it on some level, but I think the frustration is exactly that: there are actually several interesting angles here.Unfortunately the 00s were distinctly not sexy in the way she’s gesturing at. Nothing says sexy like the expansion of the global security apparatus, the “war on terror,” and, uhh, I guess the Paris Hilton sex tape? Another possible essay topic for her to take on: explaining how this 2005 Black Eyed Peas video is sexy. Her lack of awareness suggests she’s not even referencing lived experience which, along with the “no research” thing, makes it read uninformed and, ultimately, hollow. Phony even.

Chris: Let me just hit pause before getting to the “sexy” of it all and give some framework to wrap this in. The actual truth, if anyone cares to know, is that phones are not the problem. The cavemanlike perception in culture that “phone bad technology bad” is misguided. As Pete Etchells, professor of psychology and science communication at Bath Spa University, noted last year in The Guardian: “We’re repeatedly exposed to very strong negative stories about the impact of screens in the media, which changes our attitudes towards them, and in turn ends up colouring our own personal experiences.” The trick, Etchells argues, is not to think of phones “as inherently harmful or maladaptive,” but rather as “habit-forming.” Whether a habit becomes good or bad is up to a mix of contextual and situational factors.

Eliot: Right, and she is correct that we often have complicated relationships with phones, but this is really overblown. Again, there’s an interesting, deeply researched essay to be written with a lot of previous work to cite on the subject of sex and technology. There’s even an interesting personal essay here, where digital dissociation replaces embodiment among all the swipes, taps, and awkward conversations. As I said, there are a lot of angles! But the premise here really is just “phone bad.”

Chris: Exactly. It’s a frustrating read because there’s a kernel of truth to the argument that phones don’t radiate sex in the way they used to. What she says here is (mostly) true: “Nothing about our phones is sexy—from the things they allow us to do, to how they feel to use, to what they ultimately symbolize.” Of course, taking nudes, I would argue, is still sexy (given you know your angles). The issue—one that Shannon herself points out—is that “our phones aren’t solely to blame for the lack of sexy vibes in the world.” As you mentioned, there’s a major misrepresentation of decades past, and I get it; everything looks sexier when sanded off by nostalgia, But the more I scrolled, the more evident it was that the argument was floating on vibes, empty assertions, and, often, bafflingly incorrect information. As I say in the section title: “Research isn’t really my thing,” and honey, it shows. I’ll let you take the lead on the huge misread of the “Gen X Soft Club” aesthetic, which I personally didn’t know was a thing until this week.

Eliot: Honestly, I was baffled. I think everyone’s brains have been minimalism-poisoned and we’re just projecting current aesthetic values into the past to, I guess, justify our choices. Millennial Gray Brain. Gen X Soft Club was all about “natural” textures and palettes, sleek but organic, and borrowing design elements from the 70s. But it wasn’t some optimistic position on technology; the technological focus was elsewhere, as in Y2K or Frutiger Aero. Plus, it wasn’t even about some embodiment of sex. It was an advertising aesthetic!

Chris: The essay also makes the honestly batshit assertion that not only did rave culture and fitness programs only catch on in the 1990s (so bravely wrong), but that their popularity was “perhaps evidence that we feel the need to fight against” the digital age (perhaps not, and please consult a timeline).

Eliot: So much of dance music history is erased regularly, but I just can’t understand how she got here. Aside from the basic fact that raves started in the 80s via Acid House, the entire genealogy of rave goes even further back. It’s the same with the fitness stuff, like pilates was invented in the 1930s! Be serious! She’s probably thinking about 8 Minute Abs, but even that, specifically, began to emerge in the late 70s and reached an apex in the 80s.

Chris: Excuse the analogy (I’m hungry), but using two magazine spreads of Shalom Harlow from 1995 to bolster an argument that people were sexier back then because they weren’t on their phones just adds icing to the cake of confusion she’s baking. Shalom Harlow looked hot because she was hot! It’s not because she didn’t have a phone the size of a brick in her hand lol.

Eliot: Right? Like, Faye Wong was stunning no matter what she was doing. But it’s such a tired argument that goes back to the early 20th century. It was the butt of many jokes across media from the midcentury onwards. Are we really going to dismiss Cher Horowitz, a very different invention of 1995? The telephone has such a rich history of analysis and criticism, which this essay could’ve used to make a point beyond “the teens are always on the phone.”

Chris: I had a feeling when I started the essay that it’d mention the iPhone’s impact, and like clockwork, there it was. The next section begins with the 2007 launch of the very first iPhone. “The purpose of the iPhone, as it was originally conceived, was to make our lives easier. And it undoubtedly has. What we didn't—and couldn’t—know at the time was the cost,” she claims. It’s ominous, and like most arguments made by someone who boasts about not doing research, it’s also laughably wrong. The dangers of phone addiction have been written about and discussed for decades. See: research papers (“Internet Gratifications and Internet Addiction: On the Uses and Abuses of New Media,” 2004, or “Leisure Boredom, Sensation Seeking, Self-esteem, Addiction Symptoms and Patterns of Mobile Phone Use,” 2007), blog posts (“How Cell Phones Are Killing Face-to-Face Interactions,” 2007), and even WebMD pages (“When Technology Addiction Takes Over Your Life,” 2008) from that period.

Eliot: Ronell’s The Telephone Book also covered the subject in 1989, among others. The sheer lack of curiosity really clashes with her position on laziness. I would bet money that you can find a clay tablet from 4000 years ago where people complain about this or that technology making people lazy. It’s a reactionary argument. The reality is that technology creates more work. Lefebvre’s Critique of Everyday Life went deep into it across three volumes from 1947 to 1981. Was the housewife freed by modern appliances, or was her labor just redirected to other economic sectors? What in our contemporary lives isn’t specifically tweaked to create the most economic value possible, get real. What is lazy in TYOOL 2025 other than not producing value for the shareholders?

Chris: Skipping ahead slightly, I wanted to talk about her really strange inclusion of “NEETs,” which (again, unsurprisingly) she does not seem to understand. NEETs literally means “young people not in employment, education, or training.” According to Shannon, “All over the world, an entire generation of young men, often referred to as ‘NEETs,’ are robbing themselves of agency, drive, and romantic relationships through their addiction to video games and pornography.” Where to begin? Maybe with actual facts? Watch the video below or keep reading.

Here’s some easily Googleable information from the 2018 paper, “Origins and future of the concept of NEETs in the European policy agenda”: The term NEET was coined in March 1996 by a senior Home Office civil servant who had detected resistance on the part of policymakers working with the original and often controversial terms of Status Zero and Status A,” which were two technical terms that referred “to a group of people aged 16–17 years who were not covered by any of the main categories of labor market status (employment, education, or training).” See the connection? That’s called the power of doing the research, mama.

Eliot: Here it is again, in another form: they aren’t economically productive, but a NEET is a product of material conditions. Poverty, family and relationship issues, lack of access to services, things of that nature. And it’s never been about just men (what has, really?). I guess it’s easier to ignore the messiness and go for an 80s moralist rehash, but really? Is that all we can do here?

Chris: Sorry to dig in further on the weirdness here, but not only are NEETs not only men, but they are also not just men who are, apparently, “robbing themselves of agency, drive, and romantic relationships through their addiction to video games and pornography.” Claiming that “it’s heartbreaking to think that they’ll never experience true risk, true reward, or true romance” is just so weird and moral panicky lol. Yes, some guys play Call of Duty and crank it to xtube, as well as some women, nonbinary people, etc. I wanted to ask where this whole tangent even came from, but thankfully, she answered my question with her next line: “On a lighter note, aren’t we all so sick of looking stuff up?” To which I’d say… perhaps you should try it out sometime!

Eliot: Crucially, so much of her POV is something she could just do, phone or not, and chooses not to. It’s a complete abdication of agency. Why are you always making yourself available? Why don’t you yearn, or daydream, or walk around your neighborhood? You can just do these things, just like you can go out and meet someone at a bar or cafe or whatever. Is it really your phone restraining you here?

Chris: I’m not faulting the author of this essay for noticing that things feel less sexy today than they did in decades past. I’d even slightly agree with her that “what we really need is more modesty, secrecy, and discretion”—if she takes out the modesty bit. Seriously, how are you arguing for everyone to be sexier, yet you want more modesty? In regard to secrecy and discretion, that kind of self-restraint doesn’t vibe with the Thought Catalogue level of delusional essay writing that thrives on Substack (or, say, The Cut). If we’re going to hold up the flimsy argument that cell phones are what’s making us not feel sexy, I’d add tepid essays to the list, too.

Eliot: Absolutely, like yes, sexiness is absolutely down. The closest we have to a 00s-style crass sexy today is Hailey Welch, and I imagine an essay investigating that path would be delightful. Ultimately, what we have here is another contribution to the same cycle that’s been going on since well before we all carried a computer around. The argument being made is inherently conservative (“actually, I am not responsible for myself and gosh how I wish it were The Old Days”) while masquerading as flirty and fun. But it’s more sin than sexy, I’d say.

Chris: Masquerading as flirty and fun but being conservative at the core? That sounds like the battle cry of the mysterious cohort of Gen Zers who are vehemently anti-sex in survey data. Now, obviously, we’ve hammered home the point that misrepresenting the sexiness of the 1990s and 2000s is like, 80% of the problem with the essay, but I want to end with Shannon’s closing argument that “we need to allow ourselves to be restless and bored, to be less preoccupied with the opinions of others, and to look honestly within ourselves. We need to get off of our phones and hear the gravel crunching under our feet.”

Setting aside how generic and retrodden that advice is (the “touch grass” argument has been around longer than Mitch McConnell), I’d like to make one suggestion for anyone reading this. Perhaps it’s time to focus less on the “we” and, instead, spend more time holding up a mirror to your own digital habits. As Etchells said: “Crucially, habits are something much more within our own personal control to change—It takes time and effort, but if there are things about our digital diet that we’re not happy about, we have the power to get rid of them without simultaneously losing all the good things that our online lives afford us.”